An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

25th Infantry Division, 35th Infantry Regiment, Company M

Date of Birth:

June 21, 2013

Hometown:

Norwich, Connecticut

Date of Death:

January 13, 1943

Place of Death:

Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands

Awards:

Medal of Honor, Purple Heart

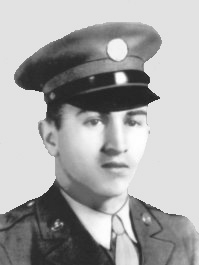

William Grant Fournier was born on June 21, 1913, to parents Olive Gadrow and Alfred Cyril Fournier, in Norwich, Connecticut. Not much is known about his early life, as his mother passed away when he was roughly one year old on Christmas day due to breast cancer.

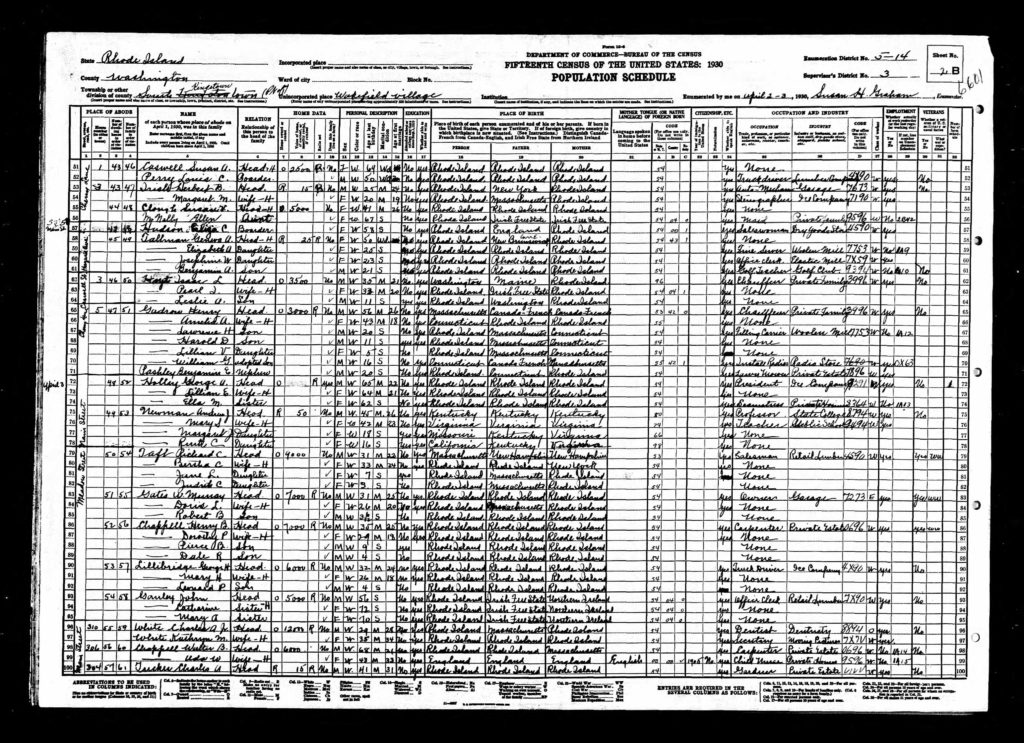

According to his great-nephew, Fournier’s father was not present in his life. Sometime after his mother’s death, Fournier moved to live with his aunt, Amelia Pashley Gadrow, and uncle, Henry Gadrow. He grew up with his cousins around the town of South Kingstown. He attended grammar school until grade eight and eventually worked in a store installing radios. When he was 18, he moved to Maine to work as a hired hand and driver.

In 1931, Fournier, enlisted in the U.S. Navy from Winterport, Maine, and served for nearly a decade, traveling throughout the Pacific. In 1937, his aunt and adopted mother passed away, and in 1939, his brother Alfred Cyril Fournier, Jr. died in an ice fishing accident. Just a year following the events, Fournier re-enlisted in military service and joined the U.S. Army.

Fournier had ties to Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Maine. During World War II, Connecticut was home to many manufacturing companies. Some of those companies were Hamilton Propellers (a propeller manufacturer), Electric Boat (a submarine manufacturer), and Pratt and Whitney (an airplane engine manufacturer). Connecticut was also part of the Women’s Land Army Initiative and ramped up food production through women with an agricultural background completing needed farming tasks.

Connecticut companies also worked to organize blood and bond drives, and many people willingly donated ten percent of their earnings to the bond drives. Connecticut citizens rallied around the war effort and not only helped to manufacture and produce vital pieces of equipment, but they also helped to both feed and fund the war effort. Connecticut really stepped up and answered the nation’s call on the homefront.

One of Rhode Island’s most important homefront contributions was the Naval Torpedo Station at Goat Island in Newport. They made around 80 percent of the country’s torpedoes during World War II. Newport was also the location of the country’s primary World War II training center for patrol torpedo boat crews. The Naval Air Station at Quonset Point was the largest naval air base in the Northeast.

In Waldo County, Maine, by the Penobscot River, many people earned their living through activities supporting river transportation. Ships were built there, originally sailing vessels, and then iron steamships. In addition to the business and industry related to the river, there were many other enterprises, including lumber mills, farms, orchards, commercial fishing, granite quarrying, and factories producing cheese, carriages, barrels, shirts, and vests.

Fournier initially enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He enlisted in 1931, from Winterport, Maine, and was able to see almost the entirety of the Pacific. During his time in the Navy, according to family members, he married an unknown Hawaiian woman and had the opportunity to see numerous different Islands. These islands soon became battlegrounds during World War II.

The family had no connection to his Hawaiian bride, and current family members still have no idea if she went on to have children, or what became of her. His great-nephew described him as a restless soul, someone who was trying to enjoy life and not take it too seriously during his travels in the Navy. Fournier served in the Navy for less than a decade, but he seemingly fell in love with the Pacific region. He eventually returned to Maine after leaving the Navy but did not stay there long.

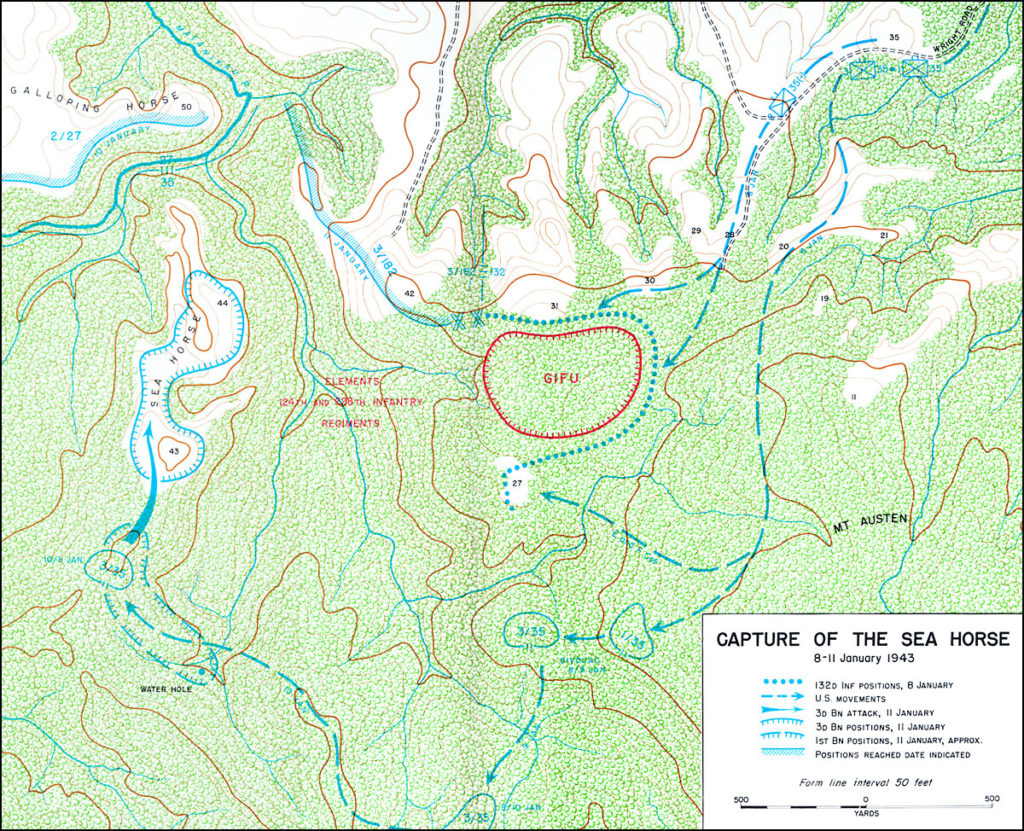

In September 1940, Fournier re-enlisted, this time into the U.S. Army with hopes to return to the Pacific. Sergeant Fournier was assigned to the 25th Infantry Division, 35th Infantry Regiment “The Cacti,” Company M, and was stationed at the Schofield Barracks, Oahu, Hawaii. Following the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, the American island hopping campaign was put in motion. The 25th Infantry Division was deployed to Guadalcanal to relieve the first Marine Division. The 35th Infantry Regiment would soon find themselves located on a ridge referred to as “Sea Horse,” and were tasked with attacking a Japanese defensive line and setting up a line of their own.

This American line fell under Japanese attack on January 8, 1943, and on January 10, in an attempt to stop the Japanese from flanking the regiment, Sergeant Fournier and the rest of his patrol opened machine gun fire onto the attacking Japanese. The Japanese were on the verge of overrunning the patrol, and a retreat was called for due to almost everybody in the patrol being wounded by the attackers.

Sergeant Fournier and Technician Fifth Grade Lewis R. Hall, some of the only non-wounded men, did not withdraw, and instead worked together to lift a machine gun, aim the muzzle, and operate the trigger. Their efforts killed 46 Japanese soldiers and broke the attack.

Technician Fifth Grade Lewis R. Hall was killed helping Sergeant Fournier hold the line, and Sergeant Fournier died three days later due to the wounds he received protecting his vulnerable brothers in arms. Sergeant Fournier was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge, Asiatic-Pacific Service Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

Sergeant William Grant Fournier was born June 21, 1913, in Norwich, Connecticut to Olive Gadrow and Alfred Fournier. Before age one, his mother died from cancer. By age six, his father left him with his aunt and uncle, Henry and Amelia Gadrow, and disappeared.

Sergeant Fournier lived and attended school in Washington County, Rhode Island. As a teen, he worked installing radios and moved to Maine to become a hired hand.

He enlisted in the Navy in 1931, serving almost a decade. In 1937, his aunt Amelia passed away. Two years later, his brother Alfred drowned.

Sergeant Fournier re-enlisted in military service in September 1940, in the United States Army, was assigned to Company M of the 25th Infantry Division, in the 35th Infantry Regiment, known as “The Cacti,” and sent to Schofield Barracks, Oahu, Hawaii.

Following the Pearl Harbor attack, his Division deployed to Guadalcanal. In January 1943, the American line fell under attack. Refusing to retreat, Sergeant Fournier and Corporal Hall charged forward to take over the machine-gun of a fallen soldier, battling heavy fire, but killing 46 Japanese. The enemy eventually retreated. Sergeant Fournier and Corporal Hall died while holding the line.

Division commander, Colonel Robert McClure, wrote:

“Your friend was killed in a brave performance of duty against the enemy. I assure you that you can be proud in the knowledge that his actions were willing, loyal, and courageous in making the noblest sacrifice a man can give – his life for his country . . . You can be certain, however, that your grief is shared by those of us who lived and worked and fought with your friend as fellow soldiers.”

Sergeant Fournier’s courage was undeterred by his great losses. We respect and honor Sergeant William Grant Fournier – may he never be forgotten and always rest in peace.

Primary Sources

“Medal of Honor.” Narragansett Times [Narragansett, Rhode Island], November 5, 1943. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

An ocean-going cargo vessel . . . Photograph. The Dodge Criterion [Dodge, Nebraska], August 3, 1944. Newspapers.com (673437707).

“Presentation of Congressional Medal Marks Signal Honor Accorded South County Solider.” Narragansett Times [Narragansett, Rhode Island], October 29, 1943. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Rhode Island. Washington County. 1920 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

Rhode Island. Washington County. 1930 U.S. Federal Census. Digital images. https://ancestry.com.

William G. Fournier. World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954. https://ancestry.com.

William G. Fournier. World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946. https://ancestry.com.

William Grant Fournier. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962. https://ancestry.com.

William Grant Fournier. Photograph. Honor States. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.honorstates.org/index.php?id=323234.

Secondary Sources

“35th Infantry Regiment (The Cacti) .” 25th Infantry Division Association, https://www.25thida.org/units/infantry/35th-infantry-regiment/.

Beem, Edgar Allen. “World War II Left a Big Footprint on Casco Bay Islands.” Island Journal, August 21, 2020. https://www.islandjournal.com/history/world-war-ii-left-a-big-footprint-on-casco-bay-islands/.

Chen, C. Peter. “Electric Boat Company.” World War II Database. Updated April 2014. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://ww2db.com/facility/Electric_Boat_Company/.

“Hamilton Standard Propeller, Three-Blade, Constant-Speed, Metal.” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (A19601414000). https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/hamilton-standard-propeller-three-blade-constant-speed-metal/nasm_A19601414000.

Krajeski, Marna Ashburn. “A Soldierly Salute: Discovering Hidden Military History in Honor of Veteran’s Day.” South Rhode Island Magazine, November 10, 2016. https://rhodybeat.com/stories/a-soldierly-salute,22434.

McBurney, Christian, et al. World War II Rhode Island. Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing, 2017.

McNaughton, James C. “The Hawaiian Department, 7 December 1941.” U.S. Army Pacific. Accessed Ocotber 31, 2022. www.usarpac.army.mil/history/dec7_printable.htm.

Patrick, Joe. Personal interview with author. August 6, 2022.

Photographs and medals or William Grant Fournier (family collection). Veterans of Foreign Wars Post, Wakefield, Rhode Island.

“Sea Horse (Seahorse) Guadalcanal Province, Solomon Islands.” Pacific Wrecks. Updated Ocotber 21, 2022. Accessed October 31, 2022. pacificwrecks.com/provinces/solomons_guadalcanal_sea_horse.html.

“Sgt William G. Fournier.” Pacific Wrecks. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://pacificwrecks.com/people/veterans/fournier/index.html.

Vachon, Duane. “A Hero Who Wouldn’t Quit – Sergeant William Grant Fournier, US Army, WWII, Medal of Honor (1913-1943).” Hawaii Reporter, July 14, 2012. https://www.hawaiireporter.com/a-hero-who-wouldnt-quit-sergeant-william-grant-fournier-us-army-ww-ii-medal-of-honor-1913-1943/.

“William Grant Fournier.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/william-g-fournier.

“William Grant Fournier.” Find a Grave. Updated August 29, 2003. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7804451/william-grant-fournier.

“William Grant Fournier.” Honor States. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.honorstates.org/index.php?id=323234.

“World War II (1941-1945).” Connecticut History. Updated May 13, 2021. Accessed October 31, 2022. https://connecticuthistory.org/topics-page/world-war-ii/page/4/.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.