An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

381st Bomber Group, Heavy, 534th Bomber Squadron

Date of Birth:

December 3, 2018

Hometown:

Val Verda, Utah

Date of Death:

June 22, 1944

Place of Death:

Abbeville, France

Awards:

Air Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster

Cemetery:

On December 3, 1918, John K. Lundberg was born into a large family in a small Utah town. His mother, Grace, was an accomplished pianist, his father, Frederick, was a talented inventor and electric engineer, and his nine siblings dabbled in everything from chemistry to politics. As was customary in the Lundberg home, John quickly gained a nickname; his was Jack.

The head of the house, Fred worked at a telephone company, affording a $3,000 house in Bountiful, Utah for Jack and his siblings. Though the family included children from three marriages, the siblings got along well and stayed close throughout their lives.

Tragedy quickly tore the family apart as four of the ten children passed in rapid succession. Jack had a sister who died of illness, another who died from an infected blister, a brother who died when a chemical experiment in the backyard created a poisonous gas, and when their last newborn died, they buried him in a pickle jar in the backyard of their house.

The strain of the funerals led to mounting tensions in the Lundberg home, and by 1940, the parents divorced. Jack and two siblings stayed with their mother in their childhood home, while the rest of the family moved out.

From 1936 to 1940, Jack attended the University of Utah, graduating with a degree in insurance. He simultaneously worked as a janitor, while his mother tended the house and his sister attended school. During this time, Jack’s father was very supportive throughout the rest of his life and provided his former wife with funding. Jack and his brother bought their mother a house in 1943, just before he married Mary Catherine Maher of Salt Lake City on November 15.

Davis County, Utah was home to four major supply depots for the U.S. military during World War II: Ogden Arsenal at Sunset, Ogden Air Material Command area at Hill Field, the U.S. Naval Supply Depot at Clearfield, and the Utah General Depot. These four depots played important roles in the war, as they housed supplies and allowed for repairs to military vessels. In addition to their military uses, these bases also provided jobs to over 33,000 civilian employees of Utah.

The Bushnell Military Hospital was another important source of employment during the war. This hospital provided specialized treatment for serious ailments, such as amputations and neurological treatments, and was one of the first hospitals to experiment with the use of penicillin. Bushnell Military Hospital helped Utah by reinvigorating the economy of Bingham City, by bringing professionals and soldiers into the town.

The war increased Utah’s population by 25%, the result of rapid in-migration in pursuit of the jobs that Utah’s military facilities presented workers.

This high degree of employment changed the landscape of Utah women in the workplace. With the men gone, Utah women were much more willing to take up careers, and the percentage of the Utah workforce made up by women doubled.

Women gained employment during the war at places like the Manti Parachute Plant, United States Geneva Works, Geneva Steel, Bushnell Military Hospital, and the Utah Minute Women. They engaged in tasks like manufacturing steel, innovating new medicinal technology, and repairing U.S. military equipment.

Not only did women want work, these ‘Utah Rosies’ were critical to helping Utah’s economy survive. They filled the void that was left when the men went overseas, and by 1944, women made up 36.8% of Utah’s workforce.

One large role that Utah played in World War II involved internment camps and prisoner of war camps. In Utah, there were 11 POW camps and four internment camps, including Topaz, the large Japanese Internment Camp, famous for its poor conditions and mistreatment of the thousands of Japanese-Americans who were relocated there.

After a brief time in the insurance business, Lundberg enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps on September 10, 1941, along with two of his brothers. Rather than entering the officer training program like many other college graduates, Lundberg attended the Aviation Cadet Training program in California for two years, then the Hondo School of Navigation in Hondo, Texas, for 18 weeks. This intensive program involved drawing maps, using compasses, and recognizing landmarks during the day and night. After completion of this training, Lundberg was awarded the rank of second lieutenant, given his Navigation Wings, assigned to the 8th Air Force, and sent to an air base in Ridgewell, England.

Once in England, he joined the 384th Air Brigade of the 381st Bomber Group, serving as one of the brigade’s navigators. During Lundberg’s time, the 381st Bomber Group participated in missions that served several purposes. First, they helped the Allies attain air superiority by bombing German airfields and planes. Second, they disconnected the German forces by bombing transportation systems. Third, the air campaign provided critical support for the infantrymen storming the beaches and countryside before and after D-Day by heavily bombing German defenses.

From December 1943 until his death in June 1944, Lundberg served as the navigator with pilot Samuel Peak on a B-17 Flying Fortress called Spare Charlie. One mission that he likely participated in was the bombardment of Oschersleben. On January 11, every member of his Bombardment Group received the Presidential Citation for Battle Honors for their work in destroying 28 fighter bombers at Oschersleben, a major German air force base.

Later in 1944, the 381st Bombardment Group was recognized as the most effective group in the entire 8th Air Force. They had the highest bombing results, and they flew 32 consecutive missions without fail–for over a month, every combat mission was successful.

On March 6, the 381st Bomber Group began targeted attacks on Berlin, the center of Hitler’s empire, a tremendous step forward in the air campaign. On April 27, the 381st Bomber Group flew their 100th mission as a group. They bombed and destroyed an important entrenched position at La Glacerie, France, one part in a series of attacks that paved the way for the invasion of France.

On D-Day, the 381st participated in two missions bombing German defenses, to support the infantrymen storming the beaches. Within the next week, the group flew nine additional missions, further assisting the Normandy invasion.

On Thursday, June 22, only two weeks after D-Day, Lundberg took lead of a B-17 airplane in a strike of a railroad station in Abbeville, France, to cut off German troop movement toward the invasion front. However, his plane flew too low, and was hit by a storm of flack from German anti-aircraft guns. The plane burst into flames, and his body fell into a patch of reeds on the German side of the river. His body was not discovered until a year later, when he was permanently interred at the Normandy American Cemetery in France. Lundberg was very good at his job, and was awarded the Air Medal with an Oak Leaf Cluster for “courage, coolness, and skill” displayed during his deployment.

On May 19, 1944, you, Second Lieutenant John Keith Lundberg, sat in your bunker in England to compose a letter to your family to be opened only in the tragic event that you would not return home. On this day, though only 25 years of age, your letter showed maturity and wisdom beyond your years, “Dear Mom, Pop, and Family, I am sorry to add to your grief, but we of the United States have something to fight for—never more fully have I realized that. The United States of America is worth the sacrifice!”

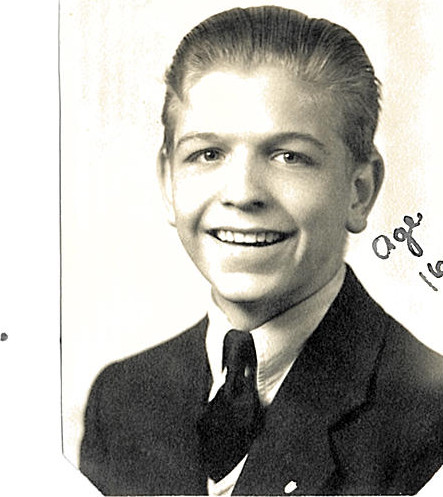

But despite the tragedy of your childhood, the maturity, intelligence, and eloquence, that is so clear in your final letter is apparent throughout your life. And though much hardship faced your family, you had a happy childhood, spending most of your time with your brothers Rich and Chick, exploring the mountains. In every childhood photograph, you had the widest grin.

Although each of your parents were twice divorced, you and your half-siblings stayed very close. Your brother described you as an intellectual, you were fluent in French, and you graduated from college. After graduation, you worked in the insurance business until the September of 1941, when you enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps.

After completing your training you were assigned to the Eighth Air Force and were sent to England, leaving home your mother, your father, your siblings, your wife, and your beloved dog, who lived a full life and has hopefully since rejoined their master. Your efforts and bravery were critical to the Allies’ victory in World War II. After the war, General Eisenhower concurred by stating while in Normandy, “If I didn’t have air supremacy, I wouldn’t be here today.”

On Thursday, June 22, only two weeks after D-Day your plane was hit by a storm of flack from German anti-aircraft guns. The plane burst into flames, and your body fell into a patch of reeds, finally discovered a year later.

Your final letter was sent to your family. As your mother read your last words to her, she wrote a poem to express her emotions. She wrote to you, “Sitting here, Jack dear. Sail on, sail on. Kneel in prayer, and silence will never dim your step.” Your mother was right. Your words and memory live on, your grand-niece wrote a school paper about you, your final letter was displayed in an exhibit in France, and your words were later recited in a speech by our 43rd President, George Bush, to help us Americans remember the sacrifices that you made, and that every soldier in every war has made. Me being here today is also proof that silence will never dim your step; your mother was right. Your memory will live on. Your sacrifice, for our freedom, which you recognized, will never be forgotten. Thank you, Lieutenant Lundberg.

381st Bomb Group, Records of the Army Air Forces, World War II Combat Operations Report 1941-1946, , Record Group 18 (Box 1582); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

“Davis County Casualties.” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed July 25, 2018. nara-media-001.s3.amazonaws.com/arcmedia/media/images/29/20/29-1936a.gif.

John K. Lundberg, Individual Deceased Personnel File, Department of the Army.

Kronmiller and Lundberg Family Photographs. 1918-2018. Courtesy of the Kronmiller Family.

Lundberg Family Papers. Ann Kronmiller Personal Collection, Springville.

“Midnight Massacre.” Time, July 23, 1945, content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,803557,00.html.

Prints: Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel – World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 – ca. 1980, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, , Record Group 342-FH (Box 35); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Prints: Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel – World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 – ca. 1980, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, Record Group 342-FH (Box 54); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Prints: Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel – World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 – ca. 1980, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, Record Group 342-FH (Box 56); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Prints: Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel – World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 – ca. 1980, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, Record Group 342-FH (Box 72); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Prints: Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel – World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 – ca. 1980, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, Record Group 342-FH (Box 76); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Prints: Photographs of U.S. Air Force and Predecessor Agencies Activities, Facilities and Personnel – World War II and Korean War, ca. 1940 – ca. 1980, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, Record Group 342-FH (Box 80); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Unit Histories, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, Activities, and Organizations, Record Group 342 (Box 238); National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Utah. Davis County. 1920 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Utah. Davis County. 1930 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Utah. Davis County. 1940 U.S. Census. Digital Images. ancestry.com.

Busco, Ralph. “A History of the Italian and German Prisoner of War Camps in Utah and Idaho During World War II.” Digital Commons, Utah State University. Accessed July 25, 2018. digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2646&context=etd

Carter, Andrea Kaye. “Bushnell General Military Hospital And The Community of Brigham City, Utah During World War II.” Digital Commons, Utah State University. Accessed July 25, 2018. digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1160&context=etd.

Glazier, Aubrey. “The Utah Homefront During WWII.” Intermountain Histories, Brigham Young University. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.intermountainhistories.org/tours/show/8.

Hallion, Richard. “D-DAY 1944: Air Power Over the Normandy Beaches and Beyond.” The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, Air Force History and Museums Program 1994. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a432943.pdf.

Kronmiller, Ann. In-person Interview. May 17, 2018.

Launius, Roger. “World War II in Utah.” Utah History to Go, Utah.gov. Accessed July 25, 2018. historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/from_war_to_war/worldwar2inutah.html.

Leonard, Glenn. “Military Installations Davis County.” Utah History to Go, Utah.gov. Accessed July 25, 2018. historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/from_war_to_war/militaryinstallations.html.

“Lundberg Family Tree.” Family Search. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.familysearch.org.

“Media Resources.” The War: Educational Resources, Utah Education Network. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.uen.org/thewar/media.shtml.

Noble, Antonette Chambers. “Utah’s Rosies in the War.” Utah History to Go, Utah.gov. Accessed July 25, 2018. historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/from_war_to_war/utahrosiesinthewar.html.

“POW Camps in Utah.” GenTracer. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.gentracer.org/powcampsUT.html.

Smart, Christopher. “WWII put Utah women to work, changed face of the state.” The Salt Lake Tribune. Accessed July 25, 2018. archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=2879356&itype=CMSID.

“381st Bomb Group.” Last modified 2018. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.381stbg.org/index.php.

“Utah World War II Stories.” KUED. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.kued.org/whatson/kued-productions/utah-world-war-ii-stories.

Wirth, Craig. “Wirth Watching: Remembering the Heroes of World War II.” Good 4 Utah. Accessed July 25, 2018. www.good4utah.com/wirth/wirth-watching-remembering-the-heroes-of-world-war-ii/163351927.

“World War II in Northern Utah.” Stewart Library, Weber State University. Accessed July 25, 2018. slangsdon.wixsite.com/wwii.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.