An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.  An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know. Unit:

63rd Infantry Division, 255th Infantry Regiment

Date of Birth:

April 1, 1917

Hometown:

Augusta, Maine

Date of Death:

March 5, 1945

Place of Death:

near the Hahnbusch and Birnberg Stone Quarry, Germany

Awards:

Bronze Star, Purple Heart

Cemetery:

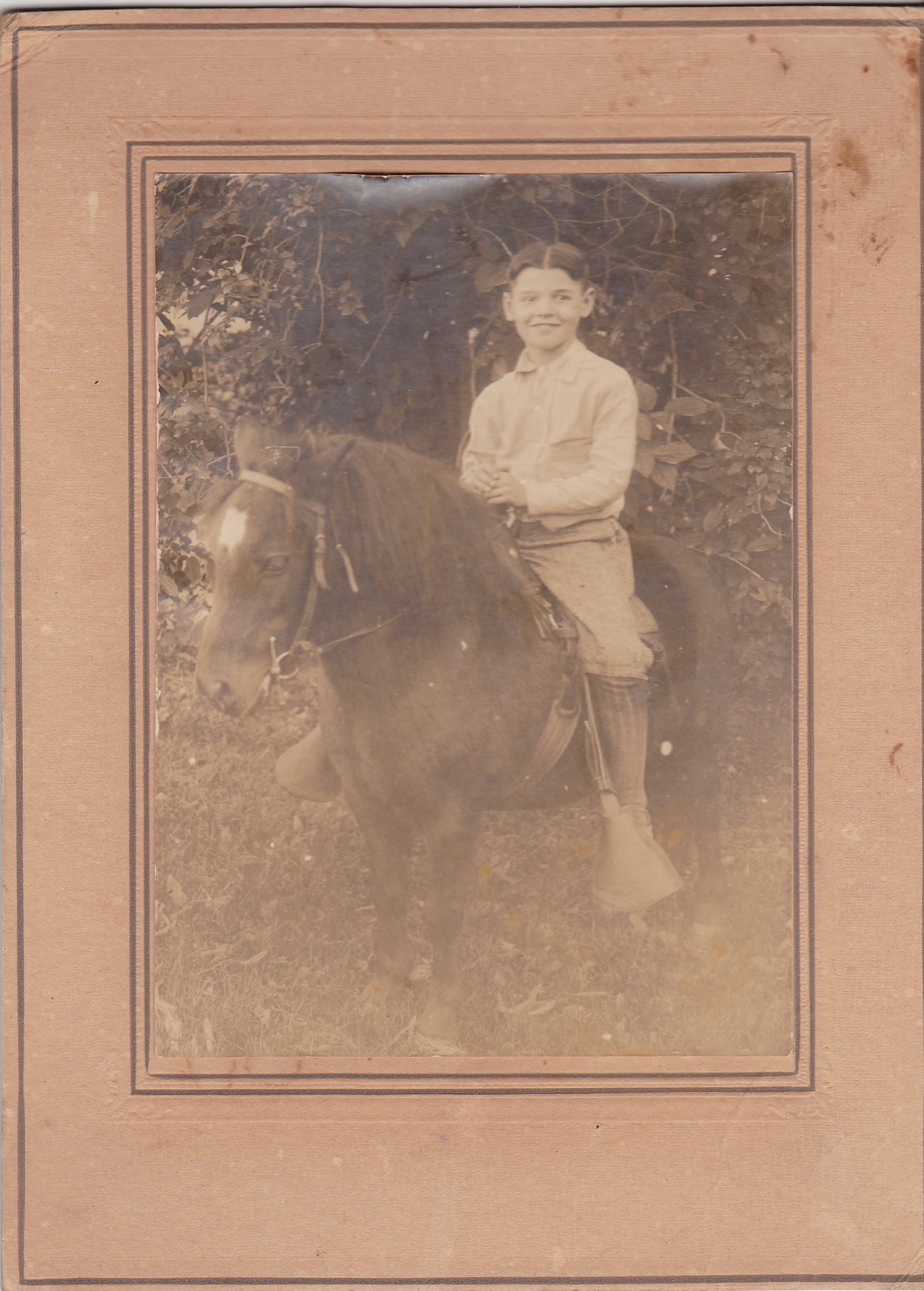

Harvey Madore was the youngest of four children born to Joseph and Annie Madore of Cyr Plantation, a small town on the Canadian border in Maine. Originally from New Brunswick, Canada, the Madore family spoke French almost exclusively. The Madores and their four children, Alma, Armand, Irene, and Harvey, made their way south looking for a better life.

They spent time in Old Town and Bradley, Maine before finally settling in the state capital of Augusta in the late 1920s. Joseph found work in a local paper mill, and Annie worked in a local cotton mill. Madore attended parochial school in Augusta. He later found work in the Edwards Manufacturing Company Mill. Over time, he became close to his sister’s friend Rita Grégoire.

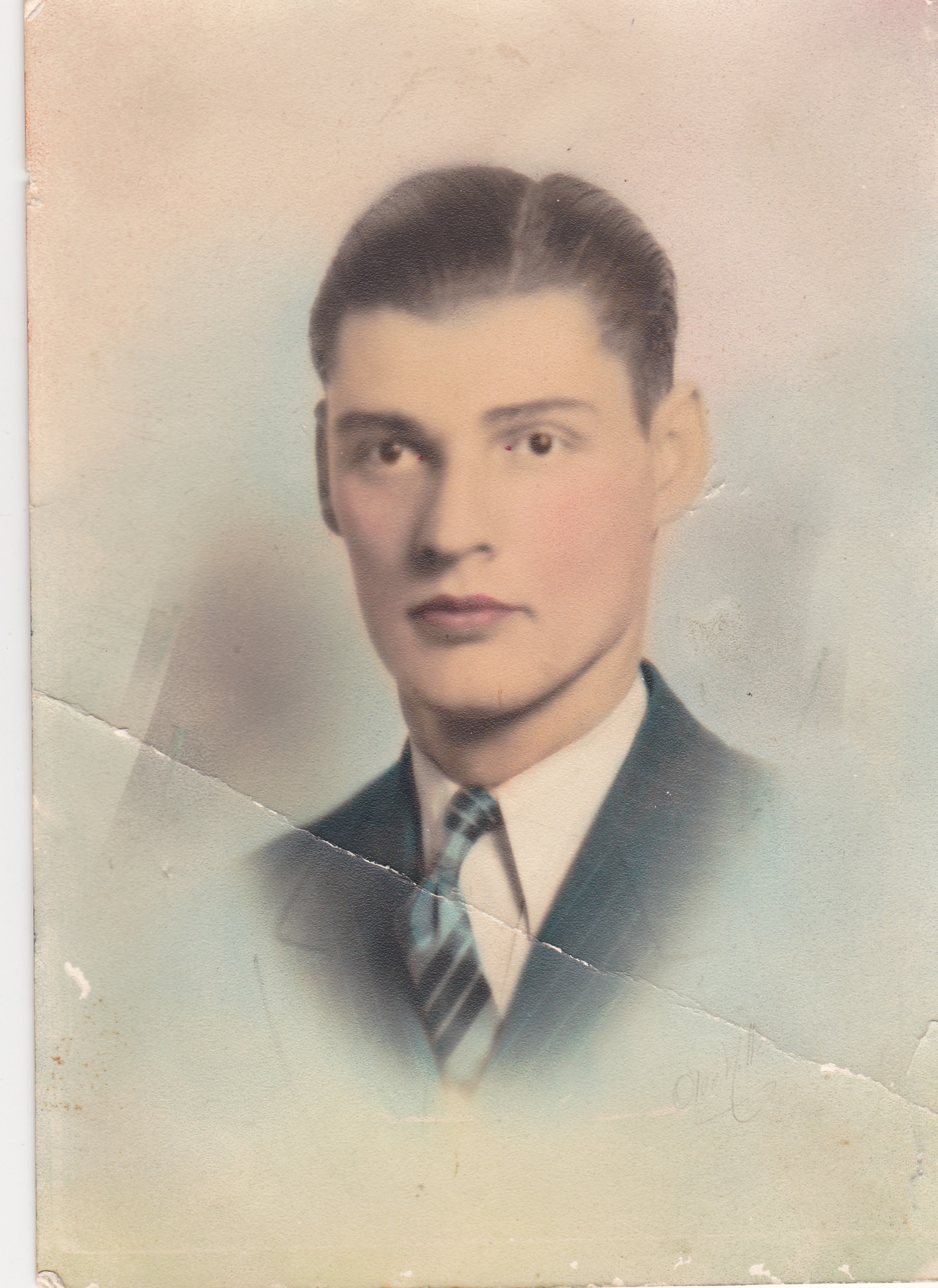

Looking to impress Rita, Madore accepted a challenge from a friend to swim halfway across the Kennebec River, which flows through Augusta, and touch the bottom. He surfaced with sand in his hand to prove his feat! Rita and Harvey married on June 30, 1941. They took up residence in a duplex on Mount Vernon Avenue in Augusta owned by Rita’s parents who lived in the apartment downstairs.

The couple had a son, Robert, on October 30, 1942. During this time, Madore continued to work in the Edwards Mill, and Rita worked for the Hallowell Shoe Company. Each morning on his way to work Madore carried his son, Robert, across the road to the woman who watched him while his parents worked.

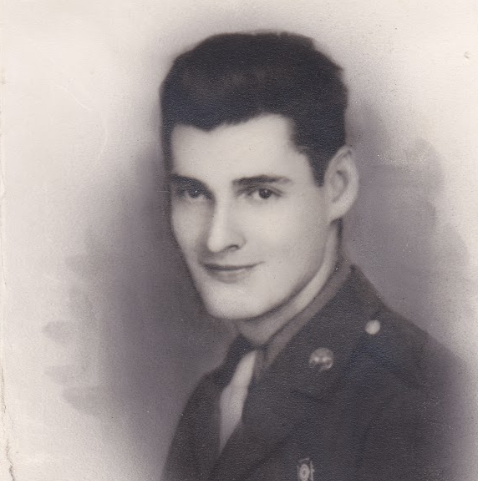

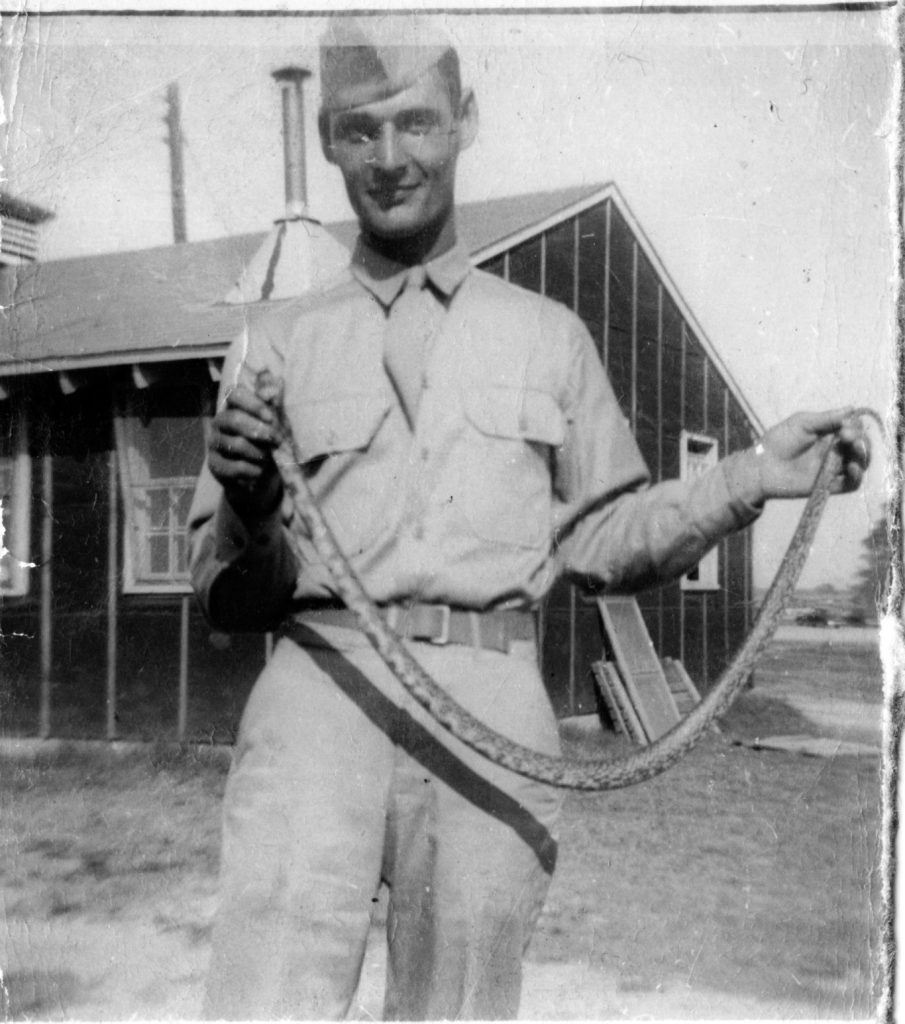

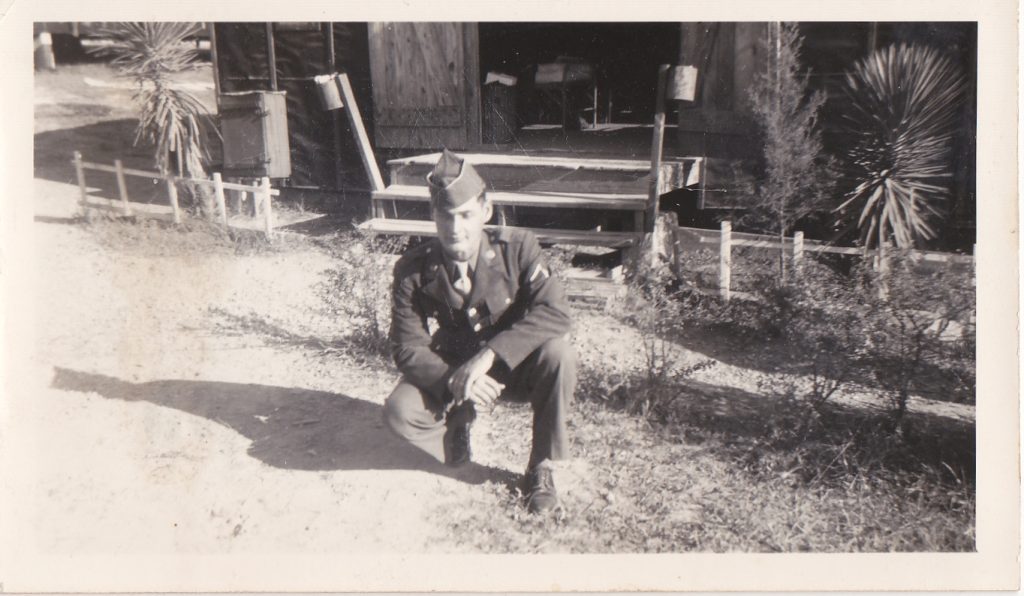

In 1944, Harvey Madore was drafted into the U.S. Army at the age of 27. He reported for duty at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and was soon transported to Camp Van Dorn in Centreville, Mississippi, for basic training. Madore was assigned to the 255th Infantry Regiment of the 63rd Infantry Division. Just after arriving at Fort Devens, he wrote a letter to Rita letting her know he had won “a few dollars” playing cards on the way there. He asked about their son and told her not to worry. During his training in Mississippi, Madore sent a photograph home of him with a grin on his face, proudly holding a snake.

After training throughout the summer, Madore and his regiment were sent to Camp Shanks, New York, in November 1944. According to his son, Madore called Rita shortly after arriving at Camp Shanks in the middle of the night. “Come see me, come now,” he told her.

Madore let his wife know that his unit would soon be shipping out for Europe and he wanted to see her one more time before they left. Rita left her son with her mother and took the first train to New York. Madore had given his wife instructions on how to find the pier and the ship.

Upon arriving, Rita was puzzled to see no ship. She asked a man nearby if he knew where the ship was located. The man nodded and pointed offshore. In the distance, still visible, was that ship, bound for France. “It left a little while ago,” the man told her. Rita had just missed him and would never see her husband again.

Private First Class Madore was assigned to the forward element of the 63rd Infantry Division. The Task Force, led by Brigadier General Frederick M. Harris, arrived in Marseille, France, on December 8, 1944. After a few days in a staging area, they moved by road and rail to Camp d’Oberhoffen, France, located about midway between Colmar and Sarreguemines.

Madore and the 255th Infantry Regiment crossed the German border and pushed toward Berlin. But shortly after arriving near the front, Madore was hospitalized on January 9, 1945, for a “non-battle” illness. According to his family, he suffered from hypothermia and frostbite while sleeping in a foxhole.

Private First Class Madore returned to his unit for active duty on January 19. In February 1945 his unit was involved in an attack between the German villages of Bübingen and Güdingen. On March 4, 1945, the regiment fought an intense battle to take control of the Hahnbusch and Birnberg Stone Quarry. By all accounts, the battle over the quarry was a bloody encounter that was terrifying and incredibly difficult. James Gregg, an infantryman who was also in the 255th Infantry Regiment, described the start of the attack:

In quick succession the shrill whistles followed by sharp explosions sprayed metal fragments among the squad…cries of “medic” were heard and the aid man hurried up to extend the limit of his ability in medical practice. The Germans had waited with patient experience until we entered the woods before commencing fire.

The regiment advanced through the woods and then commenced its assault on the quarry the next day. According to Gregg, the quarry included a complex of ditches with 20 to 30 foot high slopes. In addition, there were large pits, 30 to 40 feet deep, throughout the quarry.

On March 8, in the midst of this battle, Madore was reported as Missing in Action. On March 19 his official status was changed from “Missing in Action on March 8” to “Killed in Action on March 5.” Madore most likely died during the assault on the stone quarry, and his remains were recovered once the 255th Infantry Regiment had established control over the area. According to the medical report, Madore died from shell fragment wounds to the thorax and chest.

Madore’s body was buried in a temporary grave, not far from the German border, once his remains had been identified. A Western Union telegram on March 24, 1945, notified his wife, Rita, of his death. Rita’s mother received the news first.

She told her grandson that she had seen the telegram boy on his bike coming up the road and felt a sense of dread. When she saw him stop in front of her house and get off his bike, she knew it was either her son or her son-in-law who had died.

Rita struggled with the decision about where to bury her husband permanently, but finally decided to let her husband lie not far from where he died. In fall 1948, she decided to let her husband Private First Class Madore be permanently laid to rest at Epinal American Cemetery.

The American Battle Monuments Commission operates and maintains 26 cemeteries and 31 federal memorials, monuments and commemorative plaques in 17 countries throughout the world, including the United States.

Since March 4, 1923, the ABMC’s sacred mission remains to honor the service, achievements, and sacrifice of more than 200,000 U.S. service members buried and memorialized at our sites.

Invalid input. Please use only letters, numbers, apostrophes, hyphens, or periods.