If we stand before the engraved names on an American Battle Monuments Commission site —whether at the entrance, in a chapel, a visitor building, or a map room —we may notice the deep red hue filling the carved letters. Known as “oxblood red,” this color has become a signature detail across ABMC cemeteries and monuments.

But if we look closer, and across more than one site, we may notice this “oxblood red” is not a single shade. Over the decades, repainting, weather exposure and regional sourcing have introduced subtle variations. Some sites feature hues that lean more toward brown or pink; others show deep crimson or even bright red. In some cases, different shades coexist within the same location.

This visual inconsistency prompted ABMC’s Visitor Services and Interpretation Preservation team to investigate: What was the original oxblood red? Was there ever a single, intended shade, or were architects guided by different aesthetic visions?

Searching for the original color

In late 2024 and early 2025, ABMC commissioned preservation experts Paul Catuse of LandArc and Alexandre Nonnotte of Nacre Patrimoine to help answer these questions. Their mission: determine the original paint colors at key World War I and World War II sites through on-site sampling and laboratory analysis.

The study focused on four locations:

- Aisne-Marne American Cemetery (World War I)

- Chateau-Thierry American Monument (World War I)

- Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery (World War II)

- Netherlands American Cemetery (World War II)

These sites were selected to capture both interior and exterior applications of red paint, and to represent different time periods and architectural leadership.

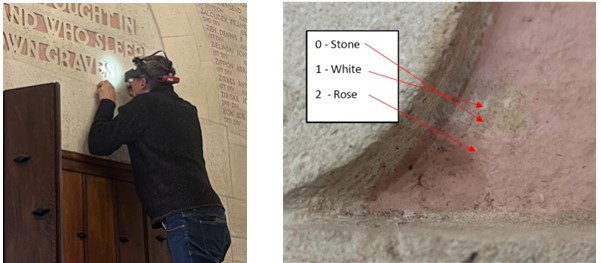

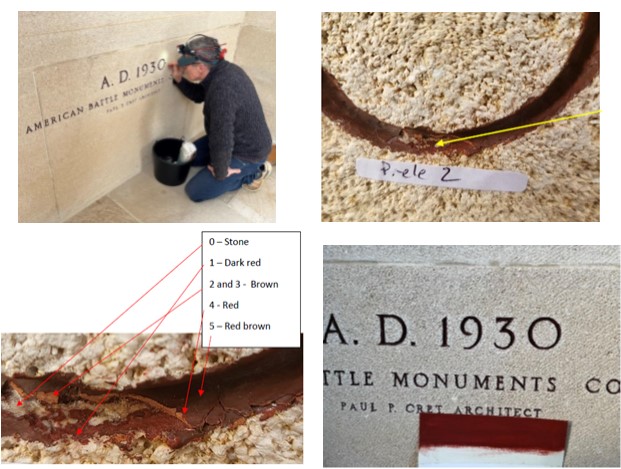

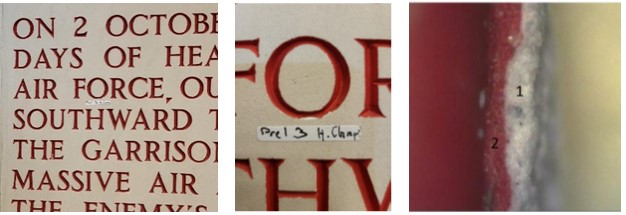

At each site, the experts carefully selected inconspicuous locations where paint was less likely to have been disturbed. Using scalpels and magnifying gear, they extracted tiny samples, some less than 5mm wide. The paint layers were then analyzed under laboratory conditions and color-matched manually with custom-blended swatches.

Surprising results at every site

At Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, inside the chapel on the Walls of the Missing, Nonnotte discovered that the original color was not red, but a soft “rose” hue layered over white primer. This color remains largely intact due to its protected indoor setting but was ultimately deemed too pink to be considered a classic oxblood red.

The team moved on to the Chateau-Thierry American Monument, where the inscriptions are frequently exposed to harsh weather. There, they found as many as five layers of paint over time. The original was a rich “dark red,” applied directly to stone without a primer. This version came closest to what many today associate with oxblood red.

In the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery map room, the first coat was a vivid, bright red over white primer. Interestingly, this site had experienced little repainting, and the current red visible today was confirmed to be original.

But the biggest surprise came from the Netherlands American Cemetery. Inside the Court of Honor, the lettering originally wasn’t red but a pale blue-gray. Though today’s letters appear reddish, likely updated for visibility, early photos suggest the lighter color was part of the original design. This discovery hints at a conscious decision by architects to use color as a functional and symbolic design element.

One color, many hues

ABMC’s goal had been to find a standardized oxblood red, but the research told a different story. Instead of a single-color standard, the team uncovered a range of original hues – each aligned with the artistic intent of individual architects and site contexts.

The differences may also reflect changing generational tastes. Designers of World War I sites favored more classical palettes, while post-WWII architects were influenced by modernist trends of the 1950s. Color choices, like architectural style, evolve with time and culture.

According to the VSI Preservation team, the notion of applying a single paint standard across all ABMC sites would ignore these nuances. These monuments were built not only as tributes to fallen service members but as cultural expressions of their time. They are art, memory and history—layered, like the paints themselves.

Preserving the original vision

As ABMC continues to maintain and preserve these sacred sites, the findings of this color study emphasize the importance of honoring the original artistic vision. Future research may focus more deeply on groups of sites from the same era or by the same architect, aiming to uncover a more comprehensive understanding of historic color usage.

While there is no single “correct” oxblood red, there is something even more meaningful: each shade carries a story, a time and a tribute.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.